Get Issuer Alerts

Add this issuer to your watchlist to get alerts about important updates.

DC’s Tools to Create and Preserve Affordable Housing

View allDecember 22, 2022

As prosperity and population in DC grow, residents with low incomes increasingly struggle with the District’s high and rising housing costs. The disappearance of affordable housing is a result of many generations of policy choices. This lack of affordable housing, particularly for larger families, puts enormous stress on family budgets and leaves many at risk of eviction and homelessness.

Black and brown residents are disproportionately harmed by the disappearance of affordable housing. Nationwide, nearly half of all Black renters are housing insecure whereas about a quarter of white renting households are housing insecure. A dramatic increase in the cost of housing in DC has led to a decades-long wave of displacement. An analysis of census data shows that in 2000, 32 of DC’s 62 residential neighborhoods were majority Black but by 2020, only 22 residential areas remained majority Black. In that time period, the Black population declined by nearly 58,000 while the white population grew by almost 86,000.

Having a safe, stable, and affordable place to call home is intrinsically connected to positive life outcomes in school performance, job retention, physical and mental health, and economic security. It ensures families aren’t forced to make difficult decisions between paying the rent or putting food on the table. When individuals and families don’t have to spend most of their income on housing, they may be able to save for and invest in their futures.

The District has many tools to create and preserve affordable housing and end displacement of residents with limited or low incomes, who because of longstanding racial inequities are likelier to be Black and brown. This guide gives a brief overview of the District’s programs designed to either create or preserve affordable housing, or to help make existing housing more affordable to residents through rent subsidies.

**Affordable for Whom? **

The idea of what’s affordable is relative. Usually, housing is considered affordable when a household spends no more than 30 percent of its income on housing and utilities. In DC, Black residents are nearly twice as likely as white residents to spend more than 30 percent or more of a household’s income on rent. This “rule of thumb” dates back to 1969 and is widely used in housing policy. While useful, the measure has its flaws—namely that it does not take into account ability to pay. A household that spends 30 percent of a $300,000 income on housing will have a lot more left to spend on other necessities than a household with a $25,000 income.

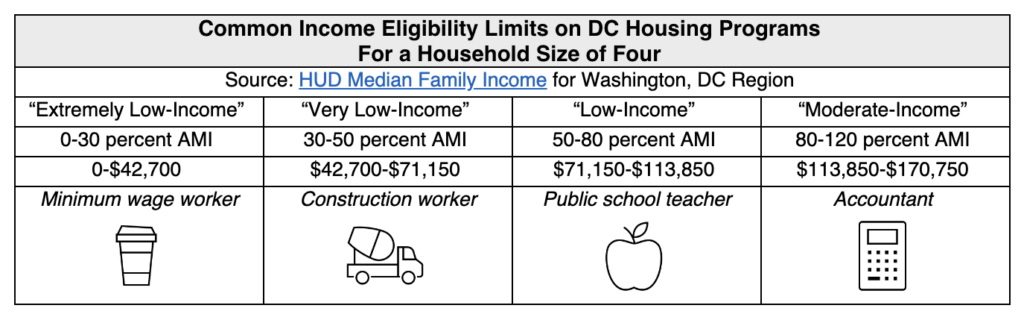

Eligibility for certain housing assistance programs is based on an individual’s or family’s income and how it compares with average income levels and costs (_Table 1). _In federal and DC affordable housing programs, a person’s eligibility is based on how their income compares with the area median income (AMI). That is the income for the middle household in the DC region, which includes not only DC but the suburbs. Currently, the Washington region’s AMI is $142,300 for a family of four, which skews higher due in part due to the inclusion of suburban regions that have higher income levels.

Some housing programs, like public housing, serve primarily “extremely low-income” households, or those below 30 percent of AMI, or $42,700 for a family of four in DC. This includes many residents on fixed incomes such as seniors living on Social Security payments. Other programs, such as project-based vouchers (see below) help “very-low income” families (under $71,150 in DC for a family of four) and “low-income” families (under $113,850). The wide range of incomes that can qualify as “low” –particularly when there is a lack of targeting or poor accountability for reaching targets—sometimes allows developers receiving subsidies to meet their affordable housing commitments with high rents and results in less housing being made affordable for those with extremely low incomes.

While families at many incomes struggle with the cost of housing in DC, where the average rent for a one bedroom is $2,428 as of October 2022, extremely low-income renters struggle the most. Most DC families with incomes below 30 percent of AMI spend more than half their income on rent, meaning many are at risk of eviction and have little left over for other basics such as health care, transportation, and educational expenses. More than 25 percent of households with incomes under 50 percent of AMI also spend more than half their income on rent.

**What Tools Do We Have for Affordable Housing? **

The current shortage of affordable housing is a result of deliberate policy and spending choices, past and present, at both the federal and local level. However, federal and local governments can and do step in to help subsidize costs. They can do that in a variety of ways, including subsidizing the construction of housing to ensure that new developments include affordable units, or by providing renters or homeowners direct cash assistance so that those residents can stay in their homes.

Production and Preservation

The District uses grants and low-cost loans to incentivize developers to create and preserve affordable housing.

-

Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) – DC’s largest affordable housing tool provides low-cost loans and grants to developers to help build and preserve affordable homes. Though the target has never been met, DC law requires that 50 percent of HPTF funds be used to produce housing affordable to those with incomes below 30 percent of AMI.

-

Preservation Fund – A revolving loan fund that allows the District to leverage private dollars in a three-to-one match to offer acquisition and predevelopment financing to developers for projects that preserve existing affordable housing

-

First Right to Purchase Assistance Program (FRPP) – When active, this DC program helped tenants with lower incomes exercise their right to purchase their apartment buildings under the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). The program has not accepted applications for several years.

Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP)

Through this program, the DC government uses local dollars, as opposed to federal funding, to help cover the difference between the rent a family can afford to pay and the full rent. The program operates through three different voucher types.

-

Tenant-based – Tenant-based vouchers are provided directly to families or individuals for use with any rental unit with priced within 185% of the Fair Market Rent in the District. The voucher stays with the family or individual, even if they decide to move to another rental unit in the District.

-

Project-based – The District awards project-based vouchers to for-profit or nonprofit developers for specific units that these developers make affordable to residents earning “low incomes,” which includes incomes up to 30 percent, 50 percent, or 80 percent AMI. Developers receiving financing from the HPTF (described above) rely on these vouchers to cover ongoing operating and maintenance costs and keep rents low for tenants with low incomes. Unlike tenant-based vouchers, these vouchers are not portable and stay with the unit. The units must be made affordable over the life of the building. Although it is not required, many project-based vouchers are awarded to developments that also provide supportive services, such as counseling, to residents.

-

Sponsor-based – Sponsor-based vouchers are awarded to a landlord or non-profit group for affordable units they make available to families with low incomes. Unlike project-based vouchers, these vouchers are portable and can be moved to another unit run by the non-profit or the landlord. Sponsor-based vouchers are awarded only to groups that agree to provide supportive services to residents housed in the affordable units.

Federal Programs with Local Administration

The federal government provides funding for public housing and a range of affordable housing programs aimed at increasing the supply of affordable housing and making existing housing more accessible.

-

Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) – This is the largest federal program for subsidizing the construction of apartments with rents below market rates. The federal government gives states and local agencies authority to issue tax credits for acquisition, rehabilitation, or new construction of housing that is affordable to households with low and moderate incomes.

-

Public housing – Funded by the federal government and operated and subsidized by the DC Housing Authority (DCHA), public housing provides deeply affordable housing to District tenants. The rent charged to each tenant depends on their income and changes as their income changes. Due to DC’s high levels of economic struggle, public housing is in high demand. In 2022, 40,000 people were on DCHA’s waiting list for affordable housing.

-

Housing Choice Voucher Program (HCV) – This federal program, administered by DCHA, operates much like DC’s tenant-based (LRSP) vouchers but is funded with federal, rather than local, money.

Legal Requirements and Restrictions

Elected officials have passed laws to incentivize or mandate the creation or preservation of affordable housing and to stabilize housing for existing renters.

-

Public land disposition – When DC sells public land for housing development of a building of ten or more units, up to one-third of the new units must be affordable for the life of the building.

-

Inclusionary Zoning (IZ) – This program requires private-market developments to set aside a share of their buildings as affordable, at 80 percent AMI for homeownership and 60 percent AMI for rentals. The District runs a lottery to allocate IZ units to people seeking housing.

-

Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) – By law, when a building owner decides to sell, tenant associations have the right either to, 1) purchase their building to convert it to a co-op or condominiums or 2) assign their rights to a developer to purchase the building. Tenants must form an association and file an intent to purchase in order to take advantage of TOPA.

-

District Opportunity to Purchase Act (DOPA) – If the tenants’ attempt to purchase their apartment building under TOPA fails, the District can intervene and preserve some affordable homes, though the District has never taken advantage of this option.

-

Rent Control – The local Rental Housing Act of 1985 limits increases in rent charged for units in certain buildings. Rent control only applies to buildings (mainly multi-unit properties) built before 1975, meaning that no new rent-controlled buildings have been added to DC’s housing supply in almost 40 years.

Paths to Homeownership

Generations of exclusionary, racist practices have led to a large racial wealth gap and homeownership gap: in DC, only 34 percent of Black residents own their homes compared with nearly 49 percent of white residents. In response to this racial wealth gap, In 2022, Mayor Bowser created the Black Homeownership Strike Force, which released a list of recommendations to increase Black homeownership. Right now, the District provides low- or no-interest loans to eligible residents through a range of programs in order to expand access to homeownership.

-

Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) – This program offers interest-free loans and closing cost assistance to people looking to buy a home in the District. The level of financing is dependent on household income and size, need, and the availability of funds. In FY 2023, the District increased the maximum loan amount from $80,000 to $202,000 per homebuyer, in response to increased property costs.

-

Employer-Assisted Housing Program (EAHP) – This program is similar to HPAP but is available only to District government employees. There is no income cap for EAHP applicants, but it is available only to first time homebuyers.

-

DC Open Doors (DCOD) – Administered by the DC Housing Finance Agency, this program offers assistance to eligible buyers for home purchase loans, down payments, and closing costs.

How Can DC Strengthen Existing Affordable Housing Tools?

A growing gap between rents and housing prices and wages for those with lower paid jobs has made it increasingly difficult for residents with low and moderate incomes to remain in the District. Given the enormity of its affordable housing crisis, lawmakers should adopt a thoughtful, holistic anti-displacement strategy that pairs long-term solutions with programs that meet residents’ urgent needs. Lawmakers must also ensure strong oversight to support the success of this strategy.

Plan for Long-term Affordability

DC will only make progress towards addressing its housing affordability crisis if lawmakers commit to making that affordability permanent. Lawmakers can achieve this in a number of ways, including expanding and strengthening rent control and ensuring that HPTF investments are both paired with ongoing operating subsidies to keep tenant rents low.

Invest in Resources for Residents with Urgent Housing Needs

While recent major investments in production tools such as the HPTF help the District increase the amount of affordable housing, progress toward production goals is slow and residents need access to housing now. The District must also provide stable and affordable housing to residents in the immediate term.

To do that, lawmakers can invest money in the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). ERAP prevents evictions by helping residents pay overdue rent and legal costs. District leaders can also increase funding for, and improve implementation of, its voucher programs to ensure that residents are able to quickly find housing that meets their needs. Policymakers can also work closely with District agencies and community-based organizations to strengthen tenant protections and prevent evictions and other forms of displacement.

Commit to Transparency, Oversight, and Improved Management

As DC invests more in affordable housing programs, lawmakers must hold DC agencies accountable to implementing these programs effectively via increased oversight. Oversight is only possible with transparency, or publicly accessible information. With regular, standardized, and clear reporting about program implementation from agencies, DC Council can make appropriate legislative or funding changes in order to meet goals such as the production of affordable housing, the provision of vouchers, or the upkeep of public housing.